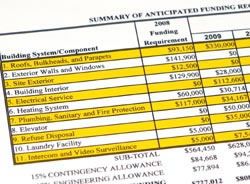

An itemized list of anticipated funding requirements helps in planning long-term capital improvement projects.

An itemized list of anticipated funding requirements helps in planning long-term capital improvement projects.

When cooperative and condominium boards undertake a large-scale capital improvement program, such as installing a new roof garden, replacing windows or a heating plant, repaving a parking lot, or restoring the facade, they take on a serious financial commitment for their building. Unfortunately, too many boards forge ahead without taking the necessary steps to adequately determine the anticipated costs associated with their plans, thereby risking a serious fiscal shortfall. Here are a few guidelines to minimize the chance that your board will find itself scrambling for additional funds once the program is underway.

Know Your Priorities

The most important point to establish before proceeding with any major repair program is to address your property's needs in the correct order of importance. All too often, a major expenditure is made on one building system just before an emergency condition develops in another building system that has not been evaluated in many years. For setting clear priorities, there is no substitute for a comprehensive building-wide survey report, such as the annual financial planning report that the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants recommends for all cooperatives and condominiums.

By having an engineer or architect periodically provide the board with a report on the estimated remaining useful life of all of the property's systems, along with a preliminary itemized budget on all recommended work items, the board will have the information needed to tackle the projects on the basis of their priority, and the preliminary financial forecasts should make budgeting much less of a guessing game. Make sure that the commissioned report analyzes all building systems and components, and provides preliminary budgets on all viable repair/upgrading options, to maximize the board's choices. The engineer/architect should also be asked to meet with the board soon after the report is submitted so that all issues regarding the condition of building systems can be discussed in detail. The board can then ask questions about how the professional's recommendations should be implemented.

Have Funds in Place

As eager as the board may be to plunge into a particular project as soon as it has its professional's prioritized recommendations, it must first realistically determine whether adequate funds are available to properly complete the required work. It is never a good idea to begin a project unless all of the necessary financing is either on hand or guaranteed to be available well before it will be needed. Otherwise, the board runs the risk that funds will be wasted on an unrealized design, such as when an engineer or architect is hired to prepare plans and specifications and the promised funds fail to materialize, forcing the project to be cancelled.

Boards should not commit to a project until all necessary funds are in hand.

In other cases, the funds that ultimately become available are substantially less than originally envisioned, forcing a last-minute reduction in the scope or quality of the intended design that could greatly hamper its visual appeal, its effectiveness, or both. For example, a shortage of funds may cause a board to eliminate a final stucco coat over a masonry wall that would have insured the waterproof integrity of the wall while providing a more uniform aesthetic appearance. As a general rule, except when obligated to act because of an emergency, the board should not commit to a project until all of the necessary funds are in hand.

Detailed Budget Breakdown

When establishing your budget for a project, it is important to have the anticipated funding requirements itemized into as many components as possible. This breakdown gives the board the flexibility to add or delete individual items along the way. Make sure that the specifications sent out to bid by the engineer or architect require the repair contractors to break down their bid into many categories. In addition, before entering into an agreement with a contractor, find out if any surcharges will be applied to the total quoted price if certain portions of the contractor's work are ultimately eliminated. The key aim here is flexibility: You don't want to be locked into a contract that forces you to complete 100 percent of the work in the unlikely event that a portion of your funding is lost or must be re-allocated to another project. Another benefit of breaking the bids down into many components is that it ensures the selected contractor is quoting a competitive price on every scope item.

A related failing of repair budgets is that they too often neglect to include common miscellaneous expenses that may be applicable to your situation, such as permit and filing fees, temporary security guard expenses, overtime wages for your superintendent, and sidewalk bridging costs. Such items can add 10 percent or more to the overall cost of a project, and if not fully taken into account during the planning stage they can create a strain on the budget, not to mention the board members.

Tight Rein on Checkbook

With a well-defined construction scope, the board should try to establish a fixed-fee arrangement with the engineer or architect to keep fees in the board's control. Even more importantly, because of the potential of expensive cost overruns, it's imperative that the agreement with the contractor also be based upon a fixed-fee arrangement. Under no circumstances should the contractor be permitted to exceed the price indicated in your agreement without receipt of a formal change order signed by an authorized board representative. The quickest way to wreak havoc on your budget is to set up an open-ended agreement that allows the contractor to make repairs on an "as-needed" unit-price basis.

The contractor should not exceed the price in your agreement without an authorized change order.

Even when an engineer or architect is administering the project part or full time, open-ended agreements almost always lead to budget problems because they are often the result of vague construction documents that do not set up sufficient guidelines of what exactly is expected of the contractor. As such, open-ended agreements also usually result in confusion among board members as to the expected budget outlays.

During the construction period, it is critical that funds be released to the contractor only after specific, detailed payment applications have been thoroughly reviewed and approved by your engineer or architect. Failure to require comprehensive payment application paperwork can result in budgetary problems because in some cases payment can inadvertently be made for unauthorized expenses that might not have stood up under scrutiny by the engineer or architect. After all, it is a lot easier to question the validity of an invoiced item before the funds have been released. Once payment has been made on an item that turns out to be disputed, the funds are usually held in the possession of the contractor until a resolution is achieved, thereby reducing the funds available to the Board, at least temporarily.

Allow for Contingencies

The most common and potentially most damaging error made when compiling a budget is failure to allow for contingency funds to cover unanticipated developments during the course of a project. As a rule, the board should maintain a minimum contingency fund of 10 percent to 15 percent above and beyond the preliminary budget established by the engineer's or architect's planning report. This is important for several reasons. First of all, the preliminary budget is traditionally established by your engineer or architect based on bids for previous projects undertaken by their office; the projections have not yet been confirmed by actual contractor bids on your particular project.

Boards should maintain a minimum contingency fund of 10 to 15 percent.

There are usually some aspects of the budget that cannot be definitive because your professional has conducted only a visual survey. This is especially true for waterproofing projects, where in many cases it is not cost effective to have your engineer or architect conduct a hands-on survey from scaffolding when developing the specifications. You would then be paying for scaffolding costs both before and during the repair process. Therefore, the engineer or architect often compiles the specification based on a preliminary projection of work quantities and requests unit price quotes from the contractors so that the contract amount can be adjusted based on the actual work quantities ultimately completed.

The primarily visual survey that is typically conducted when compiling a specification also creates a potential unknown regarding hidden field conditions. Again, it is usually not cost effective to have your engineer or architect conduct exhaustive physical tests of the existing construction details of your property to confirm that the original construction plans are accurate or that the underlying structure of the building was constructed in the proper manner.

Since there will inevitably be some assumptions made about underlying conditions, you must be ready for the possibility that the eventual demolition work, say for replacement of a roofing system, will reveal unanticipated defects or deterioration of the substructure.

Minimize Budget Surprises

Conversely, however, budget "surprises" can be minimized by having the engineer or architect perform a limited array of physical tests during the design phase, such as checking the structural soundness of a parapet wall slated for spot repair or determining whether a roof scheduled for removal contains asbestos. With the engineer's or architect's guidance, the cost of each physical test or inspection can be weighed against the value of the potential information gained.

Another reason for establishing an adequate contingency fund is that it allows the board the flexibility to add work items to the scope during the course of the repairs, perhaps even re-incorporating previously "voted-down" items that subsequently proved to have substantial shareholder support, such as a roof garden. Many times the repair contractor will offer a particularly attractive price for incorporating additional work items as part of a negotiated change order because the crews are already mobilized on the site. Having the funds available to act upon any such discounted offers is certainly desirable.

The most important reason for maintaining an adequate contingency fund is that if unforeseen conditions are uncovered, the board will be able to properly address the situation, acting from a position of strength. If your contingency fund is inadequate, you may find yourself forced to implement a "quick-fix" option that could substantially reduce the life expectancy of the entire project.

Embarking on an expensive repair or capital improvement program is a serious undertaking with many potential pitfalls. When a project fails because of a lack of adequate funding, it's no surprise that the board won't receive any appreciation for their good intentions while shouldering more than their fair share of the blame. By creating a comprehensive budget plan before proceeding, the board will start the project off on the right foot and measurably increase its chances for success.